Battling the resistance: A Wknd interview with Dr Abdul Ghafur

1 month ago | 22 Views

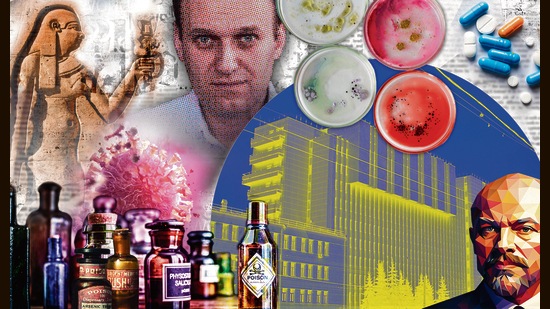

Fifteen million lives. That is the global toll of antimicrobial resistance, annually, says Dr Abdul Ghafur.

“My mission is to convince people of just how big a problem this is.”

Dr Ghafur, 53, works at the Apollo Cancer Centre in Chennai, and specialises in treating patients with persistent or life-threatening infections. These are typically people who have had their immunity battered by chemotherapy. They are particularly vulnerable to the growing number of superbugs, the virulent and antibiotic-resistant forms of disease born of people’s misuse of antibiotics (take such pills too often, or interrupt a course midway, and this is what happens; the bug evolves, and learns to fight back).

“You hold their hand, look at their face… they are crashing and you don’t have a cure. You see them every day through their difficult journey. Treating such patients, you are forced to work at the political and policy level too. You feel the responsibility,” he says.

Dr Ghafur joined this war 15 years ago, and orchestrated the Chennai Declaration of 2012, the first ever meeting of medical societies from across the country, on the issue of anti-microbial resistance (AMR).

The Declaration is still talked about in medical circles because of how effective it was.

Because it brought a wide range of the country’s best doctors, most influential healthcare bodies (government and non-government) and the media onto a single platform, it allowed debate to be followed by consensus, and then by change.

It got people talking about the dangers of AMR, and the simple steps that would help keep it at bay at the person, institutional and national levels. It got organisations to commit to funding and manpower for research.

The impact went beyond this. The Chennai Declaration sped up the publication of an extended list of not-over-the-counter medication, which included 24 antibiotics and 11 anti-tuberculosis drugs with a high potential for careless misuse.

Dr Ghafur still comes to life when he talks about it all.

He first began to worry, he says, in 2010. That’s when the superbug New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 emerged. It was so named because the Swedish patient first detected with the infection had previously been treated in Delhi. The name sparked a massive controversy, since AMR was already a global issue, and there was no evidence to support the naming of this bug after India’s capital.

Still, in India, it was a turning point, Dr Ghafur says. It accelerated the conversation on superbugs. The following year, the union health ministry formulated a national policy for AMR containment. But there wasn’t enough being done on the ground, Dr Ghafur says.

For him, meanwhile, this was a time of sleepless nights haunted by the hypothetical: What if we enter a future in which many of our drugs no longer work?

Hence, the Chennai Declaration.

***

“I spent hours every day back then, emailing, faxing and calling people, to ask them to join the initiative. I visited the health ministry every few weeks, just turning up unannounced and waiting for hours. It took months, but finally almost everyone I spoke to came on board.”

It is the Declaration that got him a seat on the jury of the £10 million Longitude Prize, which will be handed out by the British government in mid-June, to the team that has invented the most transformative new technology in the fight against AMR.

Dr Ghafur has been on the 20-member panel of international experts since the prize was first announced in 2014; they have been gathering nominations ever since.

The name is an interesting tribute to the power of such awards to change the world.

The original Longitude Prize was established in 1714, to encourage inventions that could help ships measure longitude and avoid shipwrecks. The AMR version was created on the 300th anniversary, to address a new global need.

***

For Dr Ghafur, being on the jury has offered an inside view of the most dramatic, hopeful and energised approaches to the crisis. “I’d say it’s like space science coming to the bedside,” he says. That’s the future of medicine, he adds: enthusiastic young people with wonderful ideas, being supported as they build solutions.

The energy and innovation of such entrepreneurs gives him hope and continues to drive him. Like so many, he is motivated by thoughts of his children too.

He worries for his son, Hazel Ghafur, now 22 and out in the world. And for his daughter Hena Ghafur, born in the same year as the 2010 superbug.

His work has taken him away from them, at pivotal points, he says. He remembers with distinct pain how his wife, homemaker Nishi Ghafur, 47, made her way home without him, days after she gave birth to Hena. As an infectious-disease specialist, he was racing between government offices and hospitals, desperate to explain why the new superbug was not just another bacterial infection.

His wife still talks about that day, he says. His family isn’t thrilled that even when they are watching a movie or TV show together, he usually has his laptop open on his lap.

“But I don’t regret it, because it is not just me. People around the world are doing the same. Doing more. People have dedicated their lives, risked their lives, in similar causes,” he says.

His family understands this too.

In his 50s, he has mellowed, he adds. He has begun to dedicate Sundays to his wife and children.

“I rarely go to the hospital on that day. I try to read and listen to music. I am in Calicut in Kerala on vacation this week. I take my family on more trips now, whenever my daughter tells me to. You may not listen to your wife, but your daughter has the ability to control you,” he adds, laughing with a lightness that has not appeared elsewhere in the interview.

When he can, he sneaks in some work on his book, an account of his experiences during outbreaks such as Covid-19 and Nipah.

“They are all real stories, but I am writing it as a fiction, a novel,” he says. “I have never written a story before, so I asked my daughter if she could help me, since she already has a self-published book to her name. “You know what she said? She said, ‘Yes, I can teach you, but I’m busy’,” he says, laughing again.

Read Also: spectator by seema goswami: in it for the long haul